MOVE Reporter: Generating Reports in the Backend

In this article, I explore the design and implementation of MOVE Reporter, a backend service used by MOVE to serve up reports.

Figuring out the Problem

MOVE is a data platform for transportation-related data at the City of Toronto. As a platform, it’s part data warehouse and part web application: we need the data in one place under a consistent schema, but we also need to provide end users with user-friendly access to this data.

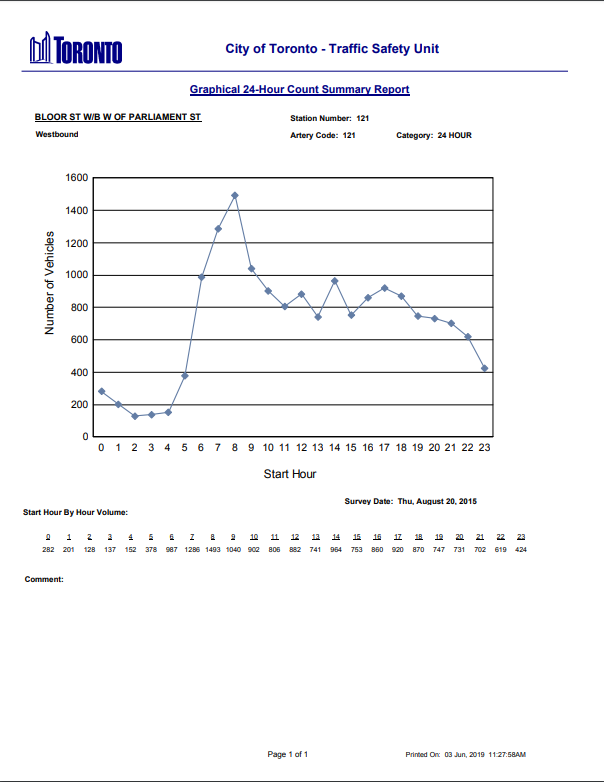

While some of our users are proficient with psql, many rely on reports designed around specific business reports. For instance, this report shows hour-by-hour volume just west of Bloor and Parliament:

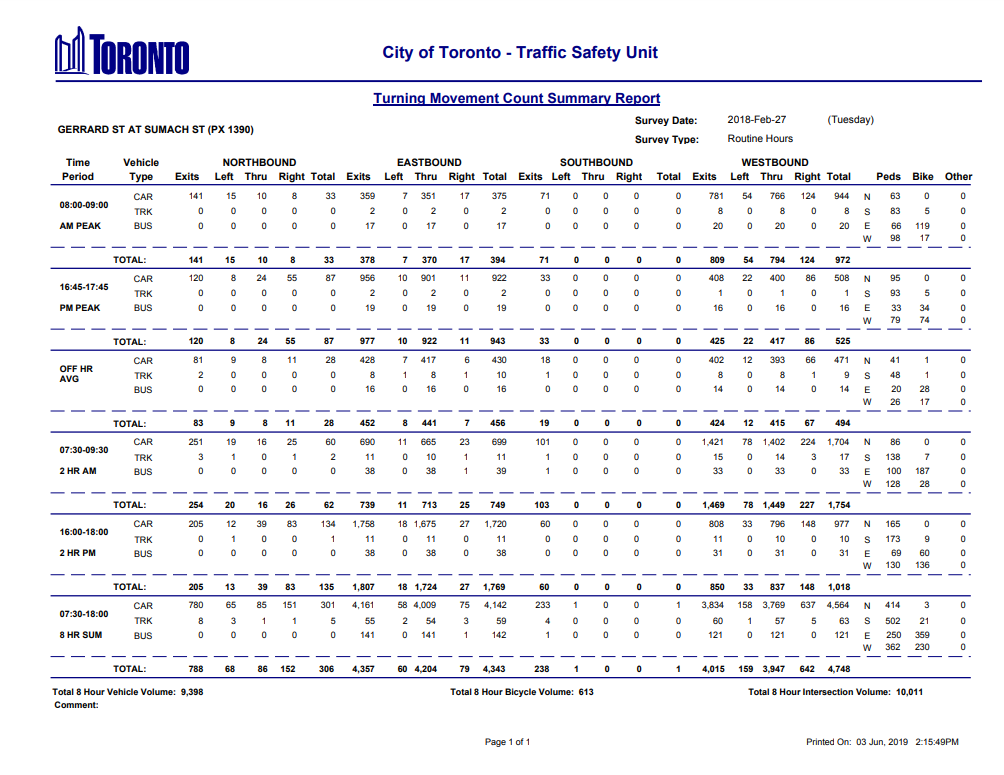

Some of these reports are more tabular in nature, like this one showing a Turning Movement Count at Gerrard and Sumach:

What looks like a dense mess of numbers to the layperson is incredibly useful to traffic engineers - for instance, when deciding whether or not to recommend installing a traffic light. Specific “turning movements” (e.g. busses entering the intersection from the east, then turning right) and summary statistics (e.g. Total 8 Hour Intersection Volume) help these engineers compare available data to the standards described in the Ontario Traffic Manual.

Often, traffic engineers will copy-paste values out of these tables into spreadsheets, where they can perform further calculations more easily. This created an opportunity: what if MOVE Reporter made it easier to get reports in various formats?

Picking Formats

Our user research surfaced several potential formats:

- web: interactive reports, rendered within the MOVE web application frontend itself;

- PDF: existing systems already provided PDF reports, so it was important to maintain access there;

- MS Word: of course, a lot of people also use Word, especially around documents to be printed or emailed;

- Excel: while some users were familiar with Google Sheets, Excel was by far the most common spreadsheet format;

- CSV: spreadsheet-compatible, and a lot easier to produce;

- HEX: common data format exported by traffic-counting hardware, and used to load data into the system.

The existing MOVE product focuses heavily on frontend use cases, so it made sense to focus on formats that were complementary to that. We’d also started to explore interactive web reports in previous releases, and had some positive initial reactions. As such, we narrowed it down to web, PDF, Excel, and CSV. In addition, we might want to provide bulk report downloads, which meant offering ZIP functionality as well.

Technical Research

We had two main engineering questions to resolve: where were we going to render these reports, and what libraries or tools would we use? That meant exploring possible answers to each question.

We document explorations like this in lab notes. Notes start with a statement of the problem, and top-level headers correspond to the main questions. Under those headers, we list assessment criteria and solutions being considered, then assess the solutions according to the criteria. This process narrows down the options by surfacing where solutions don’t meet criteria. Even where we can’t find a solution that meets all criteria, it gives us hard data to answer hard questions. Which criteria are really important? Which shortcomings can be reasonably worked around, and what might that take?

Once the exploration is nearing completion, we’ll wrap up the lab notes with a Decisions section. This section explicitly states the high-level results of the exploration, with specifics tying the decision to our stated criteria. If we can’t yet decide on a path forward, it’s our responsibility as a team to have that discussion. What does it mean for sprint planning? What will we do to move our understanding forward? Can we accept an imperfect or less well-explored solution?

You can read through our lab notes for reporting libraries and tools. Some things to note:

Languages

Right out of the gate, we limit ourselves to Python and JavaScript solutions. Why? These languages are both already in use in our project, both well-supported by City stakeholders, and both well-understood by our government partner team. They also avoid the operational overhead of introducing tools like pdflatex or html2pdf - which, though useful in the right context, are hard to justify maintaining with a small 1-2 person engineering team!

Dead Ends

In some cases, it’s possible to cull options without a full exploration. For instance, PyPDF2 is mainly designed for combining pages of existing PDFs, making it ill-suited to creating dynamic reports on-the-fly.

Finding dead ends isn’t a problem; it’s great! It means you can focus exploration on a smaller set of more promising options. Finding all dead ends, however, can be a problem: perhaps you need to search for more possible solutions, or even rethink the problem itself.

MOVE Reporter

[A] server-side implementation...avoids blocking our JavaScript processes (either client-side or server-side) on CPU-heavy report generation...It also means that we can run report generation independently of the web application - i.e. we can offer reports-as-a-service, regardless of whether people use the MOVE frontend. This is in keeping with our "data platform" objective: we want to make it as easy as possible for people to consume this data, and that means providing several ways to get it.

Technical Research — Study Reports/cite>

Enter MOVE Reporter, a RESTful node.js backend service for reports in MOVE.

API Design

MOVE Reporter provides a single HTTP endpoint that clients can call to fetch reports. Similar to the MOVE web application server, we use Hapi to implement the server:

// GET /reports?type={type}&id={id}&format={format}

ReportController.push({

method: 'GET',

path: '/reports',

options: {

validate: {

query: {

type: Joi.string().required(),

id: Joi.string().required(),

format: Joi

.string()

.valid(...Object.values(ReportFormat))

.required(),

},

},

},

handler: async (request, h) => {

const { type, id, format } = request.query;

const report = ReportFactory.getInstance(type);

const reportStream = await report.generate(id, format);

const reportMimeType = getReportMimeType(format);

return h.response(reportStream)

.type(reportMimeType);

},

});

ReportFactory is a factory for instances of ReportBase, which is a common superclass for reporting modules. We use ReportFactory to map type to a ReportBase instance, then call ReportBase#generate(id, format) on that instance.

What’s ReportFormat, you ask?

const ReportFormat = {

CSV: 'csv',

JSON: 'json',

PDF: 'pdf',

};

But wait! Where’s Excel? In the process of scoping out MOVE Reporter, we realized that CSV provided most of the functionality of Excel with much less work.

What’s JSON doing there? Well, we want to provide web reports - and one way to do that is to pass JSON containing report data to the web frontend.

ReportBase

ReportBase#generate sets up the general process for generating a report:

class ReportBase {

// other methods...

async generate(id, format) {

const parsedId = await this.parseId(id);

const rawData = await this.fetchRawData(parsedId);

const transformedData = this.transformData(rawData);

if (format === ReportFormat.CSV) {

const csvLayout = this.generateCsvLayout(parsedId, transformedData);

return FormatGenerator.csv(csvLayout);

}

if (format === ReportFormat.JSON) {

return {

data: transformedData,

};

}

if (format === ReportFormat.PDF) {

const pdfLayout = this.generatePdfLayout(parsedId, transformedData);

return FormatGenerator.pdf(pdfLayout);

}

throw new InvalidReportFormatError(format);

}

}

Overall, the process follows the common Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) pattern:

- extract data from database;

- transform that data according to report logic;

- load that data into a report.

id is a report identifier. For instance, the Turning Movement Count report above might use the intersection ID in City geospatial databases. This tells MOVE Reporter which data to extract.

ReportBase#parseId takes id, performs validation to check syntax and existence, and fetches any relevant metadata. This metadata is returned as parsedId, which ReportBase#fetchRawData then uses to fetch the underlying raw data. From there, ReportBase#transformData applies report logic: summary statistics, sub-totals, time bucketing, etc.

Finally, we render the report. JSON reports can simply return the transformed data itself, but CSV and PDF reports use FormatGenerator on the result of ReportBase#generateCsvLayout and ReportBase#generatePdfLayout respectively.

CSV Generation

ReportBase#generateCsvLayout returns an object { columns, rows }:

generateCsvLayout(count, volumeByHour) {

const { date: countDate } = count;

const year = countDate.getFullYear();

const month = countDate.getMonth();

const date = countDate.getDate();

const rows = volumeByHour.map((value, hour) => {

const time = new Date(year, month, date, hour);

return { time, count: value };

});

const columns = [

{ key: 'time', header: 'Time' },

{ key: 'count', header: 'Count' },

];

return { columns, rows };

}

columns lists the columns as they appear in left-to-right order within the resulting CSV file. rows is an Array, each element of which is an Object with values for each key in columns.

We use csv-stringify to generate CSV data from this:

static async csv({ columns, rows }) {

return csvStringify(rows, {

cast: {

date: TimeFormatters.formatCsv,

},

columns,

header: true,

});

}

The end result is separation of concerns: ReportBase#generateCsvLayout describes the structure of the CSV report, while FormatGenerator.csv renders that structure. This makes it easier to test both parts in isolation, and makes it easier to change csvStringify configuration consistently across all CSV reports.

PDF Generation

We have a similar separation of concerns between ReportBase#generatePdfLayout and FormatGenerator.pdf. Here’s the former:

generatePdfLayout(count, volumeByHour) {

const chartOptions = {

chartData: volumeByHour,

};

const metadata = this.getPdfMetadata(count);

const headers = volumeByHour.map((_, hour) => ({ key: hour, text: hour }));

const tableOptions = {

table: {

headers,

rows: [volumeByHour],

},

};

return {

layout: 'portrait',

metadata,

content: [

{ type: 'chart', options: chartOptions },

{ type: 'table', options: tableOptions },

],

};

}

Here we return an object { layout, metadata, content }. layout is 'portrait' or 'landscape', according to the page orientation of the report - in most cases, PDF reports are printed or viewed in page-oriented interfaces. metadata is used to render the PDF header, and contains details like report type, “gathered on” date for underlying data, “generated on” date for the report, and a human-readable representation of id.

content is a bit more interesting. Most reports we need to generate have some kind of table or simple chart in them. These can be described in content, together with the data used to render the table or chart. Eventually, we’ll break these out into their own rendering modules, to be called from within FormatGenerator.pdf.

PDFKit

We settled on PDFKit for PDF generation: it’s simple and robust. Making a document, adding text, and other common operations are straightforward:

function generatePDF() {

const doc = new MovePDFDocument({

layout: 'landscape',

size: 'letter',

});

// write text (to active page)

doc.text('Hello World!', 18, 18);

// draw image

doc.image(imageData, 18, 54, { fit: [144, 108] });

doc.text('after image');

// add a page, and make it the active page

doc.addPage();

doc.text('second page');

doc.end();

return doc;

}

Tables and Charts

But how to support the table and chart blocks in content? To handle this and future custom extensions to PDFKit’s base functionality, we subclassed PDFDocument and introduced methods for handling each:

class MovePDFDocument extends PDFDocument {

table({ headers, rows }, x, y, options) {

// implementation...

}

chart(chartData, x, y, width, height, options) {

// implementation...

}

}

This allows us to call these within FormatGenerator.pdf while looping through content.

For tables, we found this excellent snippet and modified it slightly. Aside from being relatively straightforward, it was also a great instructive example for learning to wrap low-level PDFKit methods into higher-level operations!

For charts, we lean on d3 microlibraries like d3-scale:

import { scaleBand, scaleLinear } from 'd3-scale';

const scaleX = scaleBand()

.range([widthAxis, width])

.padding(0.1)

.domain([...chartData.keys()]);

const scaleY = scaleLinear()

.range([height - heightAxis, heightTitle])

.domain([0, max(chartData)]);

chartData.forEach((value, i) => {

const xBar = scaleX(i);

const yBar = scaleY(value);

const widthBar = scaleX.bandwidth();

const heightBar = height - heightAxis - yBar;

this

.rect(xBar, yBar, widthBar, heightBar)

.fill();

});

We can take this even further: d3-array for max(), d3-axis to help set ticks, and so on. It’s actually quite a natural fit, as both PDFKit and SVG (where d3 is more commonly used) have very similar graphical vector primitives.

CSS in PDF?

As we started implementing PDF reports, we saw a need to maintain a consistent look-and-feel between web and PDF reports. In the web frontend, our “main theme” file tds.postcss contains all the colours, font sizes, etc. used throughout the interface…so why not keep tds.postcss as the source of truth?

We implemented FormatCss to parse tds.postcss for CSS variables, read specific values, and convert units like rem to PDF equivalents (in this case, points). We do this once during server startup, after which we can call FormatCss.var to fetch values:

const colorPrimaryDark = FormatCss.var('--primary-dark');

const fontSizeXS = FormatCss.var('--font-size-xs');

To aid in layout, we also declare FormatGenerator.PT_PER_IN = 72, and use it to initialize page dimensions:

let width = 8.5 * FormatGenerator.PT_PER_IN;

let height = 11 * FormatGenerator.PT_PER_IN;

if (layout === 'landscape') {

const temp = width;

width = height;

height = temp;

}

Frontend Downloads

We considered using the Content-Disposition header to set a filename. For now, however, we went with FileSaver.js, which polyfills window.saveAs to download files:

methods: {

// other methods...

onSelectDownloadFormat(format) {

if (this.report === null || this.downloadLoading) {

return;

}

const type = this.report;

const countInfoId = this.activeCount.id;

const categoryId = this.activeCount.type.id;

const id = `${categoryId}/${countInfoId}`;

const options = {

method: 'GET',

data: { type, id, format },

};

this.downloadLoading = true;

reporterFetch('/reports', options)

.then((reportData) => {

const filename = `report.${format}`;

saveAs(reportData, filename);

this.downloadLoading = false;

});

},

},

reporterFetch(url, options) is a wrapper around window.fetch; in this case, it returns a Blob containing the rendered CSV or PDF report.

Where Next?

MOVE Reporter was deployed to AWS for the first time at end of last week, where it’s happily serving CSV and JSON for 3 of our 7 target report types and PDF for 1 of 7. Our next step is to expand coverage: 4 of 7 reports are considered high-priority, and we aim to cover those 4 with CSV, JSON, and PDF support before moving on to any others.

As we expand coverage of report types and formats supported, we’ll be looking to simultaneously improve testing coverage. Traffic engineering is an engineering discipline in the capital-E sense of the word. While MOVE Reporter can’t fix issues in the underlying raw data, it can take steps towards a more reliable, accurate, and trustworthy reporting layer for transportation-related data at the City of Toronto.

This emphasis on trust aligns nicely with our near-future plans to open-source MOVE. For the first time, traffic engineers at the City of Toronto will be able to see exactly how the software they use builds the reports they depend on. By isolating reporting logic as described above, getting it out in the open, and committing to ongoing improvements in testing, readability, and documentation, we allow these processes to speak for themselves - and that’s powerful.